Breadcrumb

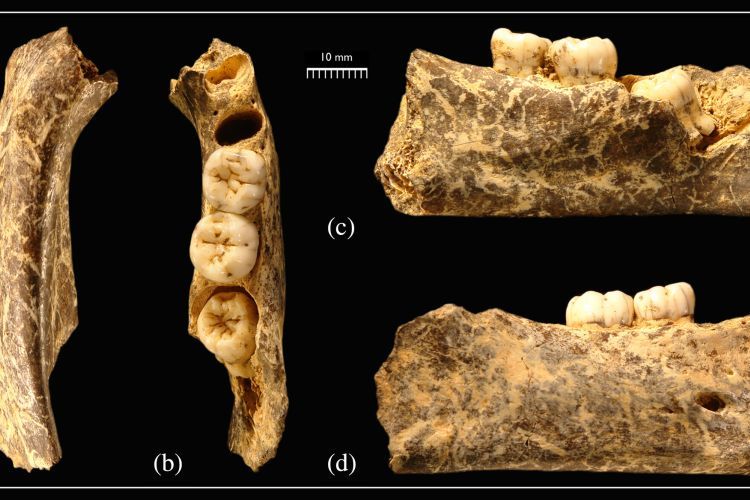

Early Neanderthal mandibular remains from Baume Moula-Guercy

Inferior (a), superior (b), medial (c), and lateral (d) views of this adolescent Early Neanderthal mandible.

What is it?

The article provides a comparative analysis of mandibular remains from the last interglacial period at Baume Moula-Guercy.

What problem does it aim to solve?

The exact time when certain Neanderthal-like features in the jaw first appeared, and when those features became more common, is still not well understood. However, jaw remains found in Eemian deposits (around 120,000 years ago) at Baume Moula-Guercy offer new evidence that could help answer these questions.

How does it work?

The study uses developmental and morphological characteristics to link these remains to Preneanderthal and Early Neanderthal groups, showing affinities in mandibular features such as mental foramen position and molar crown characteristics.

What are the real-world implications?

This analysis helps understand the variation in Neanderthal morphology between 246,000 and 115,000 years ago, and the evolution of distinct Neanderthal traits observed in later periods.

What are the next steps?

The shape and structure of the jaw provide clues about how the Neanderthal face evolved, but there are challenges in interpreting this due to the different age ranges of the fossils in each group. Also, the variation within and between these groups is limited because many samples come from just one small population. To improve understanding, researchers suggest reanalyzing jaw features, collecting more data, and using new methods to make better comparisons between existing samples.

“The importance of our recent publication lies not so much in the description of these new remains, but in our uncovering the fact that the unique face of the Neanderthal is likely not a product of a long evolution in periglacial environments. Rather it appears now that there were developmental changes in the craniofacial region in populations that lived long after the Last Interglacial (80,000 to 30,000 years ago) that resulted in the unique facial structure that is one of the defining features of the Neanderthals. This is a major breakthrough in understanding the ontogeny (growth and development) and evolution of the craniofacial complex in the Pleistocene and it helps us better understand developmental factors underlying the evolution of the modern human face.” says Gary Richards.

Source

Early Neanderthal mandibular remains from Baume Moula-Guercy (Soyons, Ardèche), The Anatomical Record, 2024

Authors

Gary D. Richards, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry

Rebecca S. Jabbour, Department of Biology, Saint Mary’s College of California, Moraga, California

Gaspard Guipert, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Fondation Albert Ier Prince de Monaco, Paris, France

Alban Defleur, IPHES Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana I Evoluci o Social, Tarragona, Spain